Of all the techniques that could be used to study ancient texts, there are a few that stand out as being both very important and largely understudied, being either ignored in practice or taken on faith due to the lack of relevant expertise or accessible tools. The ones that come to my mind right now are these:

Of all the techniques that could be used to study ancient texts, there are a few that stand out as being both very important and largely understudied, being either ignored in practice or taken on faith due to the lack of relevant expertise or accessible tools. The ones that come to my mind right now are these:

- Paleography. Understood in general terms and largely regarded as a matter of deference to the experts, this may not have an abundance of practitioners but is at least widely respected and has a huge impact on historical studies. The other two mentioned may be envious of such wide respect and acceptance.

- Computer-Aided Textual Criticism. There are those who truly believe that completely-thoroughgoing eclecticism is the only answer, there are those who would like to do something more but have no idea how yet, and then there are the few who come back from their tours through the land of “Coherence–Based Genealogical Method” textual criticism and try to convince the other two that it’s really worth visiting sometime.

- Stylometry. Of the three, perhaps the most confusion surrounds these techniques, and a large part of it is due to the confusion and unresolved questions that still persist among the experts. Due to a combination of widespread superficial familiarity with the studies and the contradictions from those using some kind stylometric method to reach controversial conclusions, stylometric “results” are most often cited with some degree of skepticism (except, of course, when credulously cited as a conversation-stopper).

The first of these two subjects truly are fascinating in their own right, and there are no doubt some others like these that I didn’t mention. But let’s talk about stylometry.

I personally find this field of study fascinating and can summarize, roughly, some of the material that I have read. There are more-detailed treatments, of course, but I’ll try to give a general impression of things.

A (Very) Brief History of Stylometry

(1) Some time in the late 1800s, someone thinks it’s a good idea to try to distinguish between various authors solely on the basis of sentence length variation. (Turns out he’s mostly wrong, not that it can’t be used as part of a healthy variety of metrics.)

(2) Some time in the early 1900s, someone figures out something called Zipf’s law. It turns out that this is still pretty useful even today as a description of several phenomena. It has something to do with all those hapax legomena (words appearing once), dislegomena, trilegomena, and so on, and what proportion of each tend to fall in each category.

(3) Some time in the mid-20th century, someone thinks it’s a good idea to use that kind of thinking in order to find out the extent of someone’s vocabulary as a way to determine authorship. (Turns out he’s mostly wrong, unless provided with truly massive amounts of input.)

(4) Some time in the mid-20th century, Mosteller and Wallace provide one of the first studies that seems to show that there might be something to this whole ‘stylometry’ thing after all. They worked on the basis of word frequencies, a sort of Bayesian reasoning, and a choice between two authors (The Federalist Papers).

(5) Also in the mid-20th century, A. Q. Morton appears on the stage and sets the tempo of the discussion for a while. One of his relatively-good ideas is exploited by several authors; it involves taking some relatively-frequent words and measuring their frequencies in fixed-size samples (expecting that the ‘sample’ will show observed frequencies closer to the correct author than anyone else).

(6) His name is, unfortunately, also associated with some less-well-conceived approaches, including a so-called ‘QSUM’ technique advanced in the 1980s. Fortunately, some of the better ideas, the product of earlier discussions and attempts, emerge in the 1980s as well. Quote:

The idea of using sets (at least 50 strong) of common high-frequency words and conducting what is essentially a principal components analysis on the data has been developed by Burrows (1987) and represents a landmark in the development of stylometry. The technique is very much in vogue now as a reliable stylometric procedure and Holmes and Forsyth (1995) have successfully applied it to the classic ‘Federalist Papers’ problem.

(7) The fruits of the digital age start to show in the 1990s. Large, freely-available electronic corpora and cheap, very-powerful personal computers combine to quicken the pace of research considerably.

(8) Instead of merely looking at the frequency of single words, what if we looked at the frequency of bi-words (two words occurring in a certain order) and tri-words (three words occurring in a certain order)? What if we also looked at bigrams (two characters in a row) and trigrams (three characters) or other n-grams? And many more possible features of a text were found to be exploitable to good effect.

(9) Stylometry is widely recognized in the scholarly literature to consist of, primarily, two components: (a) pre-processing and processing of text towards identification and measurement of such features of a text and (b) a form of principal component analysis or pattern recognition, primarily to determine which of several texts is the closest match to the test sample(s). One could also add (c), an analysis of empirical results, using works of undisputed authorship, in order to find out how secure, based on that data, any particular conclusion is when the technique is applied to real world problems.

(10) Much of the recent research has been attacking the “pattern recognition” part of the problem, testing various different techniques for combining a wide variety and large number of measurements down to something manageable that can be used as a basis for the decision as to which texts seem closest to which in style. This research has benefited from advances in Artificial Intelligence and from the similar techniques being developed for cognate applications, including image recognition and voice recognition. A wide variety of mathematical techniques are employed today, and studies frequently focus on the question of which method of combining all the individual measurements provides the best final results.

Three Ongoing Issues

(1) One enduring issue in stylometric research may be called “the problem of small numbers.” Or, rather, the problem of how to handle small numbers. Most formal statistical analysis operates fairly well with adequately-sized expected populations. Even just five (or so) expected occurrences of something in a sample can work well with standard statistical measures and techniques. The question, then, is whether anything useful can be done with the (majority of) measurable data that doesn’t conform to the requirements for most formal statistical analysis. This problem is especially relevant when attempting to innovate with techniques that have reliability even with smaller sample sizes. (Treating this as more of a ‘pattern recognition’ problem instead of a strictly-defined statistical problem has led to progress here.)

(2) Another issue is the problem of attributing authorship when a “closed” list of candidate authors is not available. This is often considered a difficult problem, and it was especially common to avoid broaching the issue in earlier research. This has led to the misunderstanding that stylometry can operate only when the real author is known to belong to a definable set of known authors with extant text. It’s true that many studies, even today, have operated on this assumption (and, in some controlled settings or online settings, there are ample opportunities to find situations just like this). It’s also true that those situations where this assumption can be taken as a known fact lead to more reliable results (in some degree) than those situations where this assumption cannot. But there is certainly research being done on the question of how best to determine whether the author of the tested sample text belongs to some known candidates or likely belongs to none of them. This is sometimes called an “open” attribution study (open to candidates other than those on the list) or is considered the general problem of whether two texts likely have the same author or likely do not (or whether it cannot be said).

(3) A third problem has been identifying the cause of differences in style or similarities in style; more specifically, identifying the ways in which various causes are more likely to manifest themselves in the stylometric data. Related to this problem are all the purposes for which stylometry is used other than authorship attribution. Stylometric methods have been applied to other problems such as chronological authorship studies over a single author’s lifetime, ‘genre prediction,’ ‘translated text prediction,’ ‘era prediction,’ ‘gender prediction,’ ‘ideology prediction’, ‘intelligence prediction,’ ‘positivity or negativity assessment,’ and even ‘fraud detection’ (principally in the domain of online reviews). In the domain of authorship attribution, the question is often posed: what is likely to remain invariant for an author (and what is not), even across time or across genres, and what is likely to distinguish authorship (instead of, merely, some other commonality)? One subject that is potentially the most complicated is called ‘adversarial authorship detection’ (of interest principally in the intelligence community, as an attempt to find techniques to detect and overcome the adversarial techniques of writing that are foiling the initial techniques of authorship detection). In every specific example, the question is basically this: what is the ‘signal’ and what is the ‘noise’? What can be used to discriminate between many potential authors or options and pick the right one?

These three issues are closely related to three general goals:

(1) Achieve results with smaller test samples or smaller training samples.

(2) Determine whether confidence can be placed in the closest match, thus reducing the ‘false positive’ rate (and often with the goal of also maintaining an equally-low ‘false negative’ rate).

(3) Increase the frequency with which a test sample is matched with the training sample of the actual author (general accuracy), even with a large number of training samples to select among.

In practice, achieving these goals is a compromise among them. Generally speaking, the rate of accuracy will be reduced by smaller samples, stringent level of confidence tests, or a larger number of options from which to choose the correct one. Improvements in method often focus on making the tradeoffs involved in this compromise less severe.

Let’s Go Back… to the Future!

If words such as standard deviation already have you itchy and perhaps reaching for the Wikipedia page, the math typically used in contemporary stylometric techniques will appear to be pure jabberwocky. I will admit that I can struggle with it. It makes sense to go back to that “landmark in the development of stylometry” in 1987, when the use of a set of high-frequency words as a method of attributing authorship was demonstrated to constitute a reliable method. We’ll discuss something similar, which is based on my own “basic stylometry” program written recently.

The goal here is just to get a basic overview of the ideas and to convince the reader of its overall reliability in general terms. To that end, and because I believe that the public perception of stylometry has all-too-frequently been marred by the controversial claims of particular conclusions based on it, all the examples that follow will involve some church fathers that generally do not become hot-button issues when it comes to authorship attribution: Justin Martyr, Athenagoras of Athens, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen.

By the way: if you ever see a stylometric technique being used that has not first been verified as a reliable technique in relatively-unambiguous cases, that’s a very clear red flag! There is absolutely no reason not to treat the claim that a stylometric method is reliable as a hypothesis, one which can be tested (and possibly established) only by an assessment of its performance with real-world data where the conclusions are already known by other means. Failing to perform any experiment of such a kind, before applying the method to a controversial or unknown case, is pure pseudoscience.

Step (1) – Decide a Sample Size and Stick to It

It’s common to see multiples of 500 used for sample sizes in authorship attribution studies: samples of 500 words, 1000 words, 1500 words, 2500 words, and so on. The important thing is consistency. This is completely under our control, so it’s simplest and best just to “hold it equal.”

The text being tested can be broken into multiple samples, each tested independently, or might be the length of a single sample. All the authors being tested as possible candidates for authorship of the text being tested should be relatively extensive, enough to get an idea of the range of their stylistic variation.

Step (2) – Count How Many Times the Features Appear in Each Sample

If the feature is the number of times the word “and” (Greek kai) appears, then we want to know the actual number of times that the word appears in the test sample and in all the other samples.

Step (3) – Calculate the Mean and Standard Deviation for Each Candidate

The mean is, of course, just an average: sum up all the numbers and divide by the number of samples from that particular candidate.

Wikipedia describes standard deviation as “a measure that is used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of data values.” In visual terms, a larger standard deviation will mean a flatter graph, and a smaller standard deviation will mean a narrower graph. The flatter graph will have more area under the curve at the extremes, while the narrower graph will have more under the curve at the center.

We want these numbers for the next step, where we compare the observed frequency (in the test sample) of each feature to the mean and standard deviation of the feature in the individual candidates.

Step (4) – Skip a Few

Okay, let’s just avoid the rest of the mathematical technicalities. The bottom line here is that these kinds of calculations will let us know which candidates seem more likely to have produced the observed frequency in the test sample (based on how much area is under the curve at that point on the graph where the observed frequency is–lots if the observed frequency is right under the center ‘hump’ of the curve) and which candidates seem less likely to have a test sample with the observed frequency (little if the observed frequency is under the long ‘tails’ of the curve).

Let’s just show a normal curve, then, to illustrate.

The normal curve. σ = standard deviation.

For the purposes of the program, there will be a computed value for every (candidate, feature) pair that says how close that candidate is to the sample on the basis of the feature. The closeness depends on where the observed frequency, in the test sample, falls in that particular candidate’s normal curve plotted on the basis of all the given candidate’s samples, with respect to that feature.

Different candidates have different curves because they have different means and standard deviations, as computed above. On this basis, we can differentiate between the candidates.

Step (5) – Magic Happens

Or principal component analysis. Or something like that.

The point of this step is that, instead of having a list of (candidate, feature) pairs, we can just get a single value for each candidate: a single number representing how close the sample is to that candidate.

Step (6) – Many Candidates Enter, One Candidate Leaves

Step 6 is simplicity itself. Simply pick the candidate with the maximum value (or minimum value, depending on how exactly the numbers are being represented). The candidate that has that one number that represents being closer to the sample than any of the other candidates, “wins”!

Is That ALL?

It could be. But in the particular program that I wrote, I wanted to look at one more thing.

I wanted to be aware of how likely it is that none of the candidates wrote the sample text.

So I used this one simple trick.

In addition to the regular list of real candidates, I also used a second list of phony candidates.

I called these phony candidates the ‘controls’, and I picked them because they were (a) in the right language and from the right time period and (b) not likely to be the actual author of the text.

The theory is, if some more-or-less random author off the street walks in and starts providing better matches for the sample text than any of the so-called real candidates, maybe none of the guys on the initial list wrote it in the first place.

Not that the random fellow did either–we just said that it’s not likely that he did. So the conclusion in that case is that it seems like we have no idea who wrote it, but likely none of the candidates did.

It worked out surprisingly well, considering the simple tools used (techniques that are about 30 years old) and the ambitious aims (an “open” authorship attribution study). Not perfect, of course, but enough to know that the method was really getting at something that pointed to the likely authorship of texts.

Let the results speak for themselves.

First Case – Justin Martyr

I began posting the results of my ‘basic stylometry’ program on the Biblical Criticism & History Forum as I went through things. I got a lot of valuable feedback. It also kept me motivated (and kept me honest, as I updated results piecemeal over several days–one of the open secrets of [bad] science being that inconclusive or negative experimental results often just never get published).

The first attempt was simple. I took a section of the ‘First Apology’ and a section of the ‘Second Apology’ and I let them be the test samples. I used the full text of the ‘Dialogue with Trypho’ as one of the candidates. And I used a few other texts as ‘candidates’ and a slew of other texts as ‘controls.’ Both texts were most closely matched with the ‘Dialogue with Trypho.’ This wasn’t much, but it was a start. Justin is typically ascribed with all three.

Second Case — Athenagoras of Athens

The second attempt was also fairly simple. The work known as ‘On the Resurrection of the Dead’ was divided into two samples. I used the full text of ‘A Plea for the Christians’ as one of the candidates. And I used various other ‘candidate’ and ‘control’ texts also, for comparison. Both samples from ‘On the Resurrection of the Dead’ were most closely matched with ‘A Plea for the Christians.’ Again, this was a good start. Both are attributed to Athenagoras of Athens.

At the same time, I also compared two extant samples of books 2-3 of Irenaeus’ Against Heresies against a candidate author represented by the extant text of book 1 of Irenaeus’ Against Heresies. Both of the later samples from the work matched most closely to the text of the first book of it.

Neither of the first two cases could be considered very significant tests of the method. I needed more.

Third Case — Clement of Alexandria

This was much more detailed than either of the previous two. The post is here.

In summary, the following relationships were observed among the texts (roughly 90% accuracy):

- 10 out of 14 times, the sample from the ‘Paedagogus‘ was matched with the text of the ‘Protrepticus‘.

- 6 out of 6 times, the sample from the ‘Protrepticus‘ was matched with the text of the ‘Paedagogus‘.

- 16 out of 16 times, the sample from the ‘Stromata‘ was matched with the previous two.

- 2 out of 2 times, the sample from ‘Who Is the Rich Man Who Will Be Saved?‘ matched with the previous three.

- 2 out of 2 times, the samples from ‘Excerpts from Theodotus‘ matched with the first three.

The so-called ‘Letter to Theodore‘ (of ‘Secret Gospel of Mark‘ fame) could neither be authenticated nor disproven as authentic with this method. As was seen from the small frequencies of the ‘words’ measured in a sample of that size, it would be very difficult to use Clement’s habits of style to identify a text only 749 words long with this method. The ‘Hymnus Christi servatoris‘ and the ‘Eclogae propheticae‘ were also too short to be tested with this method.

Huh? Why Not Test the Letter to Theodore? Why?

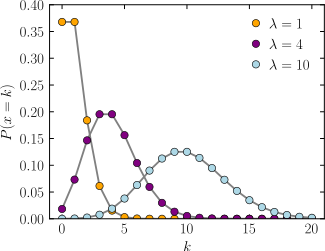

I had the opportunity to explain a little bit about why short samples are a problem with this particular method. It’s worth quoting here. The root of the problem is the ![]() Poisson distribution.

Poisson distribution.

The frequency of a given word in a sample from an author of length N (randomly occurring with some chance, call it X) is actually better represented by a Poisson distribution. The Poisson distribution looks more like a normal distribution with sufficiently long lengths and/or sufficiently high probabilities of occurrence for any particular word. So the normal distribution can approximate the Poisson distribution with higher expected averages for the observed frequency of words in samples.

But, if the expected number of sightings is very low, then the Poisson distribution just looks like a lumpy mess shoved up against the left side of the number line, and it’s practically impossible to tell whether a sample with a certain actual observed frequency (like, say, … 0, 1, 2 or 3) came from any particular Poisson distribution… and thus impossible to say who wrote the thing with that particular observed frequency of the word ‘peri‘, for example.

Wikipedia has a chart:

The small, useless, lumpy, scrunched-up-against-the-left Poisson distribution is shown in orange. With a small sample, most ‘words’ being considered as candidates for distinguishing authorship have distributions that look roughly like that…. for every single author.

(Side note: The technique is about thirty years old. This is not set in stone. Some methods could be better at dealing with this. The smallest samples that I’ve seen used in the literature about stylometry with some good results, albeit using online English text, were only about 250 words long.)

Fourth Case — Origen

Origen provided a splendid arena in which to showcase the capabilities of the algorithm, including the ability to identify potentially dubious works, without knowing who the real author might be.

All the work and all the results are documented, in extensive detail, on the forum.

The results in summary, not including those texts not tested or too short to say anything meaningful.

| 102 of 119 (# matches to Origen) / 85.7% | Certainly Origen |

| 40 of 52 | Contra Celsum |

| 4 of 4 | De principiis |

| 16 of 18 | Commentarii in evangelium Joannis (extant books 1-32) |

| 18 of 19 | Commentarium in evangelium Matthaei (books 12-17) |

| 3 of 3 | Exhortatio ad martyrium |

| 6 of 6 | De oratione |

| 15 of 17 | Philocalia |

| 6 of 7 (# matches to Origen) / 85.7% | Probably Origen |

| 2 of 3 | Homiliae in Lucam |

| 1 of 1 | Epistula ad Africanum |

| 1 of 1 | De engastrimytho (Homilia in i Reg. [i. Sam.] 28.3-25) |

| 1 of 1 | Homiliae in Exodum |

| 1 of 1 | Selecta in Exodum, Fragmenta ex commentariis in Exodum |

| 1 of 4 (# matches to Origen) / 25% [cumulative 83.8%] | Possibly Origen |

| 1 of 1 | Homiliae in Leviticum |

| 0 of 1 | Dialogus cum Heraclide |

| 0 of 1 | In Jesu Nave homiliae xxvi (fragmenta e catenis) |

| 0 of 1 | Libri x in Canticum canticorum (fragmenta) |

| 8 of 15 (# matches to Origen) / 53.3% [cumulative 80.7%] | Possibly Origen, Mixed Authorship, or Author Unknown |

| 6 of 11 | In Jeremiam (homilies 1-20) |

| 2 of 4 | Fragmenta in Lucam (in catenis) |

| 4 of 30 (# matches to Origen) / 13.3% | Likely Not by Origen, Author Unknown |

| 2 of 20 | Fragmenta in Psalmos 1-150 [Dub.] |

| 1 of 4 | Commentarii in epistulam ad Romanos (I.1-XII.21) (in catenis) |

| 1 of 4 | Fragmenta ex commentariis in epistulam ad Ephesios (in catenis) |

| 0 of 2 | Scholia in Apocalypsem (scholia, 1, 3-39) |

| 8 of 10 (# matches to Gregory) / 80% | Not by Origen, Possibly by Gregory Nyssenus (or Someone Else) |

| 8 of 10 | Fragmenta ex commentariis in epistulam i ad Corinthios (in catenis) |

| 10 of 11 (# matches to Clement) / 90.9% | Not by Origen, Possibly by Clement of Alexandria (or Someone Else) |

| 2 of 2 | Fragmenta in Jeremiam (in catenis) |

| 5 of 5 | Expositio in Proverbia (fragmenta e catenis) |

| 3 of 4 | Fragmenta in Lamentationes (in catenis) |

The basis for deciding whether a text was “possibly Origen” or “likely not by Origen” is mentioned in this post (using Fisher’s exact test).

This doesn’t seem to contradict scholarship on Origen or on the patristics severely, in general terms, which is good. The ones that “should” have been identified as certainly Origen’s, according to scholarship, have been identified as certainly Origen’s. The ones that “should” be considered “[Dub.]” are considered dubious. While there may be some expansion of the “dubious” category, the texts claimed are not among those asserted to be part of the ‘core canon’ of Origen’s texts; they frequently are attested only through the catenae, which have something of a reputation for occasional misattribution.

On the other hand, there are some issues with the possible rewriting of Origen (especially in excerpted fragments), differences arising from certain selection biases when a continuous text of the author is not available (again, for excerpted fragments), or possible differences due to genre (in the homilies for example) or the difficulty of finding where the quotes end and begin in an efficient manner (especially scriptural quotations), so it’s possible (possible) that a few more texts end up in the “dubious” categories than possibly (possibly) should be.

The suggestions that Clement of Alexandria or Gregory Nyssenus could be responsible for some of this text are intriguing and deserve further investigation. (But only intriguing, because, as far as I know, there is no real reason to think that either of them are the actual author, rather than someone that might be relatively close in style to the unknown actual author.)

Based on Origen, the rate of accuracy (for positive identification) with this method seems to be somewhere between 80% and 86% when using sample sizes between 2500 and 5000 words long.

But How Good Were the “Negative” Results for Origen?

Conventional authorship attribution analysis is required to answer this question. With the help of various members of the forum, we were able to identify a few strands of existing scholarship that could be found to support not only the more-obvious “positive” results (that some texts were likely by Origen) but also the “negative” results (that some texts were likely not by Origen).

From a book mentioned in the discussion, I noticed two footnotes regarding Fragmenta in Jeremiam (in catenis). John Clark Smith writes: “Nautin, 1:30, doubts the authenticity of this fragment because it has a different exegesis of Jer 1.10 than that given in Hom in Jer 1.6.” (link) And, again, John Clark Smith writes: “This is another fragment which Nautin, 1:31-32, uses to bring doubt upon the usefulness of these fragments. He claims because Origen only mentions Aquila and Theodotion in the commentaries, and that the ‘nations’ are not seen in this way in other works, that the fragment is not genuine.” (link)

Another poster (Tenorikuma) noticed references that may be taken to imply the inauthenticity (or the plausibility of inauthenticity) of the Expositio in Proverbia and the Scholia in Apocalypsin.

A Newly Discovered Greek Father: Cassian the Sabaite (Sup Vigiliae Christianae 111) makes close analyses of the parallel wording used in various ancient commentaries, and some of these might have relevance. On p. 292, the author notes the similarities of Origen’s wording to Evagrius:

“Origen’s catenae-fragments are phrased after Evagrius’ vocabulary, and probably some of them were compiled by him. Cf. Origen, selPs, PG.12: 1085.23; 1676.9; expProv, PG.17: 241.1–2; 245.53.”

ExpProv, that is, Expositio in Proverbia, is one of the candidates you have for being written by someone else. p. 304, n. 27 reads:

“This analysis is a plain and direct influence by Evagrius, who probably quoted from Origen explaining Proverbs 7:6–9. The passage is attributed to both Origen and Evagrius, with only a small portion omitted from Origen’s ascription, which I canvass in the Scholia in Apocalypsin, EN IXg. See then, Origen, expProv, PG.17.181.5–16 and Evagrius, Scholia in Proverbia (fragmenta e catenis), 89 (& Expositio in Proverbia Salomonis, p. 87)…”

Another poster (Andrew Criddle) offered this comment.

The authenticity of the scholia to the Apocalypse has been repeatedly questioned see the footnote here. They probably come from a post-Origen work which made use of Origen and other sources.

This is certainly not, by any means, any kind of last word. Nor do we have adequate data to pronounce on exactly how well the program performs with negative results. (To reach such a conclusion in a rigorous way, we would want a different setup, where we use works that we were absolutely certain were not by Origen or any of the other candidates or controls. We’d also want to use other authors besides Origen.)

But we’ve already seen, just by scratching the surface, some doubt in the scholarship about 3 of the 8 texts identified as likely not by Origen. And, of course, one of the texts is already noted in the Thesaurus Lingua Graecae, in its title, as “[Dub.].” That brings it to 4 of 8 with some ease. I’d say that is at least a welcome sight, even as more analysis and testing is necessary to know just how good or bad things are, exactly, with the accuracy of the method’s detection of negative results.

Well, What Do You Know?

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this little trip through some basic stylometry. More importantly, I hope that you may have a richer understanding of the fundamentals of how stylometry works and a deeper appreciation of the potential of stylometry to provide information regarding authorship attribution. Most of all, I hope that you might be willing to check for a stylometric analysis next time before making a decision about the authorship of a given ancient text. We don’t get much real benefit out of the results of these techniques, even if they may have some level of confidence and rate of accuracy established through testing, if they don’t happen to carry any confidence with people in practice.

If you haven’t seen the ‘technique’ verified as to its accuracy by the experimental method with verified empirical data, naturally I fully support you in your healthy skepticism! If you don’t trust the practitioners, I don’t really blame you for that either. It’s for this reason that I’ve made the basic stylometry program that I wrote (rudimentary and “beta” though it is) publicly available.

If you’d like to use it, you should start by visiting this thread at the forum (ignoring whatever is unhelpful–I understand that the write-up is very inadequate) and asking me any questions you may have. In particular, I suggest downloading this file to have some texts with which to work.

I’d like to improve the program, both in its methods and its interface. Let me know what you think so far.

Peter, this is wonderful work–thank you. It deserves wide recognition.

I do have one or two minor quibbles. First, it’s been suggested that Fisher’s Exact should not be used with fixed significance levels–there’s a brief summary on Wikipedia. This is only a very minor point, since you use appropriate caution when interpreting your results 🙂

Second, Homiliae in Exodum and Homiliae in Leviticum are listed without the qualification that they are, in fact, only fragments of the Greek text of these works. This is probably because that is how they are listed in TLG. But to make it clear to your readers, these are only fragments of the Greek text. Homiliae in Genesim is correctly listed as in catenis in TLG, but for whatever reason TLG does not list the homilies in Exodium and in Leviticum as such. (Perhaps I should write them a note about that.) Your readers should not imagine that you are in fact testing the entire text of Hom. in Ex. and Hom. in Lev.! (Which we only have in Latin.) I have no doubt you are well aware of this, of course.

In the case of Hom. in Ex., the Greek text is drawn from Procopius and from a couple of catenae fragments; in the case of Hom. in Lev., it is taken from Procopius and from the Philocalia. The selections in the Philocalia are noted for evidence of editorializing (see for example Carla Noce’s comments in Studia Patristica v. 43, pp. 451-452, currently viewable on Google Books), and that may explain the ambiguous results for Hom. in Lev.. (See the rest of Noce’s article for a comparison of the Greek and Latin, and see her footnotes for problems regarding the text of Procopius!)

FWIW, you probably already know this as well, but the sources for the Greek can be observed by looking up the work in TLG, noting the critical edition (for these homilies it is Baehrens, GCS 29 i.e. Origenes 6), and clicking the “View text structure” link. That gives the page numbers in the critical edition. We can then find the GCS volume on archive.org (https://archive.org/details/origeneswerke06orig), which as you no doubt know Roger Pearse helpfully provides links to (http://bit.ly/1FlEve1), and look up the first page of each selection, where Baehrens shows the source of the Greek passages. (In the case of the catenae fragments for Hom. in Ex., Baehrens appears to include these separately on p. 230ff, as explained in FOTC 71 pp. 39-40. They are not used in TLG.)

As one last note, perhaps it makes sense after all that Hom. in Ex. and Hom. in Lev. are not listed in TLG as in catenae since their selections just come from the Philocalia and Procopius’ Commentary on the Octateuch. So this might just be an ambiguity of notation. (However, Noce notes that the Greek text of Procopius does in fact come by way of catenae. Nevertheless, that may be a technicality.)

All very useful notes. Thank you very much! And thank you for the kind words.

[…] Peter Kirby gives a detailed treatment of stylometry in Biblical Studies […]

Well now, this is what I desire most, a machine that will unravel things, reducing my cogitation levels. Seriously, I wonder if stylometry could be applied to the Clementine literature. After reading Robert Eisenman, I have become aware of this literature as it references the 1st century, but I also sense much that is overwritten, modified, &c. I sense a number of authors and ‘streams of consciousness’. Perhaps it is just to diverse to apply stylometry. Thoughts?

Wow, Peter…

What a wonderful resource you have created here…I am fairly new in my Christian walk, seven years back this coming Easter (’26)…And I am really now just finding a fire for learning scripture (at age 62) and have a yearning to serve my Lord and His Church as He guides me.

Thank you for your years of effort and for following your guidance in creating such an incredible resource…I’m sure God truly appreciates and honors your efforts in His service…as do I.

Alberto ‘Kodi’ Volkmann